My grandfather lived a life that was full of movement. He was always very active, a hard worker, and seemed to have endless amounts of physical energy. I remember watching him work as a child, fascinated by his strength. His tools and tool shed took on totemic value for me. He did plumbing and masonry, electric wiring and landscaping. He built his own house (with the help of many conscripted volunteers – he was also an excellent motivator/recruiter). He drove trucks and tractors. He was always in motion, even very late in life. He was always chopping or sawing or hauling or lifting. And yet, through all the movement, there was also stillness. In all the chopping and hauling, there was also a great deal of reading. He lived a life that was rich and full. It was full of friends, accomplishments and experiences, and it was also full of books.

He was born and raised in a small town in rural Appalachia, all forests and tobacco fields. To a certain extent he embraced that identity wholeheartedly. But he didn’t stay there. He left to study, after that he left the country. He was not running away, but he was running. He lived and worked in Israel for many years, and throughout the Middle East. He eventually came back to the small town of his youth. Robert became “Bobby” once more. You cannot escape where you are from, and he didn’t really want to (although “Bobby” did make him wince a little). He came back willingly. He knew no other home.

No, you cannot escape where you are from, but you also cannot help but be changed by leaving it. He was different, and couldn’t help it. He loved fishing, but he also loved art museums. He loved country cooking, but could also discuss the merits of Moroccan couscous. He loved sports and poetry and beauty. He was about as globally conscious as a person could be, but still rooted to a very particular piece of earth. Literally rooted. He bought land and started a tree farm, preaching the gospel of sustainable development. He also preached the gospel of Jesus. He was an anomaly; in other words, he was a person.

Throughout his life and travels he amassed a lot of books. When he passed away I took some time to go through his library. It was a time of parsing. Not that anyone was itching to throw all his old books away, but some order did need to be made. Plus, I knew it was a task I would enjoy. As I considered each book, the question I tried to ask myself was: do we really need this? As it turns out, the answer was almost always yes.

Yes, we really do need my grandfather’s worn-out old copy of Bruno Bettelheim’s Children of the Dream, because to throw it away is perhaps to forget that he had more than a passing interest in communal living and intentional communities (the 70s happened to everyone). Yes, we do need an old copy of Yigal Yadin’s book on Masada. It helps us remember that he was actually a volunteer on that dig, and that he had a great interest in archeology (I kind of think an interest in archeology was a requirement for everyone who lived in Israel in the 60s – needless to say, James A. Michener’s The Source was in his library as well).

Yes! We do need these books, we need his library. For although not everyone goes for the crumbling library aesthetic, to take it away would be to take away a vital part of his memory. In some ways his library was like a wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling monument to his life. A bookshelf biography.

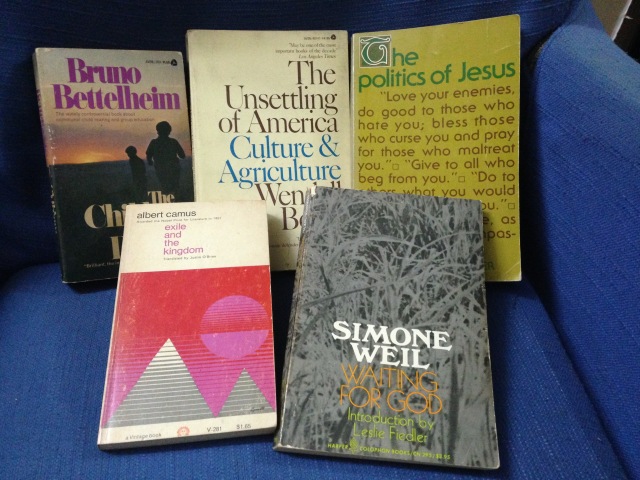

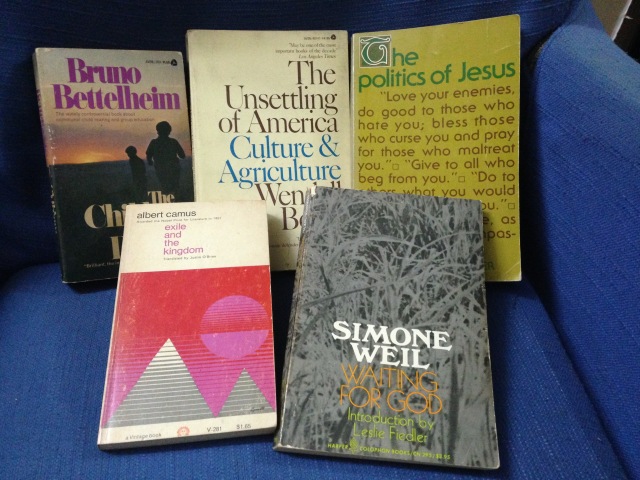

Some scavenged gems!

My goal was not to select which books to get rid of (I could never do that!), but I did pick out a few that we should absolutely keep. Ultimately, I am sure my selection says more about me than about him. But that is just as true of the memories we store in our minds as it is of the books we store on the shelf – we choose which to keep and which to toss.

Naturally, I gravitated to the books that I found interesting. But I was also drawn to the books that had connected us in some way. They were all his books, but the ones that we had discussed, or argued about, or even recommended to each other were special. If the library represented his whole life, these books were moments we spent together. Three of them stuck out especially to me because of the memories they revived.

I found Exile and the Kingdom by Albert Camus – Vintage edition, 1965. Seeing it reminded me of another time I went through his library, while he was alive. I found it, took it off the shelf and started reading it. After awhile he came in and saw what I was reading and asked me a few questions about it. We talked about Camus for a while, and I don’t remember much of what he said, but he did make a comment that I remember. He said, “That is what people used to call avant-garde in my day.” I loved two things about this.

First, I loved that he knew Albert Camus is no longer avant-garde. When he said avant garde, he meant, I think, something that is cutting edge and experimental. But he also meant something else, which I suppose is inevitably connected to the cutting edge and the experimental – something that is scandalous.

He knew that Camus is no longer avant-garde in either sense of the word. I loved this because it is not a given. We all tend to think that whatever was new and cool and made parents angry when we were young stays that way. Somehow the things that scandalized or outraged the world in our youth remain forever scandalous or outrageous. It is as though people find a point in time and decide to stop there, forgetting that the rest of the world moves on. I guess it makes sense, we all need a point of reference. But that is why his observation struck me. How many of us are aware of our own point of reference?

Second, I love that he read Camus when it was avant-garde. Or at least kind of. True, by the mid 1960s reading Camus was not really that new or exciting or scandalous anymore. He had already won his Nobel Prize and died in a car accident by then. He was mainstream, but that didn’t make him any less scandalous in my grandfather’s particular milieu, which was very religious and very conservative. It’s not like he was reading Sartre or anything (heaven forbid!), but still, he grew up where dancing and movies were considered morally wrong – a lot closer to Paris Kentucky than Paris France. I am sure my grandfather raised some eyebrows in reading that book. He didn’t say that he did, but it seemed implied in the way he said avant-garde. He said it with mischief.

Actually, I do remember one other thing he said about Camus. Something about his work “lacking hope.” But he didn’t say it in a mean-spirited way. He said it with empathy and understanding. And he wasn’t really wrong. That was kind of the point Camus was making through the Absurd. Yes, there is in his work a kind of frail, human hope that is actually more courage to face the hopelessness than it is real hope. Yes, Sisyphus does get to pause for a moment on the top of the mountain before heading back down to head back up. But that is a far cry from authentic hope. My grandfather was a believer, very much so. He had hope. But he also understood that hope is absurd in the face of all that life brings. He believed in the truth, but was not afraid of questions, even difficult questions, since the truth, if it is true, will not be destroyed by questions.

One of the books in my grandfather’s library is a hardcover edition of James B. Pritchard’s Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, a classic sourcebook, used by multiple generations of students studying the ancient Near East. I remember we talked about it one time, since I was taking a course on ancient Egypt and we were assigned another book by the same author in that class. We discussed the value of first hand sources, and how things are inevitably lost in translation (the translation through language, but also through time).

He showed me his book, which was damaged, and told me that it was one of his most prized possessions. I didn’t understand what he meant at first, but then he told me the story of how he came to buy it. He lived in Israel when Jerusalem was divided, and had made a few trips over into East Jerusalem, which at the time was a part of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. He said that there was a bookstore on Saladin Street that he visited every time he crossed over, and that this book was on display in the window of the store. Every time he went to the store he would stare longingly at the book, but it was too expensive, so he never bought it. Then the Six-Day War happened, and East Jerusalem was united with West Jerusalem.

The next time he went to Saladin Street, he didn’t have to go through a checkpoint, or through no-man’s land, but he found it much changed. During the fighting, the street had been dotted with mortar fire every 100 meters or so, making it impassable for cars. One of the mortars fell right in front of the bookstore, and obviously shattered the front window. Pritchard had taken a direct hit. A huge hole had been bored through the front cover, and through the first half of the book’s pages. Because of the damage, the book was considered worthless, but he still wanted it, now more than ever, so he bought it for next to nothing.

He slowly flipped through some of the pages to show me, and there were still flecks of shrapnel in it, almost 40 years later. Some of them were so small they looked like metal dust. Looking at it made me shiver. If this kind of damage was done to a thick, hardcover book, imagine what it would do to human flesh.

The story behind the book reminded me of the Linear B tablets left by the Mycenaeans, which archeologists discovered in places like Knossos and Pylos. Unlike other ancient texts, written on papyrus (which preserves surprisingly well in low-humidity), or carved into stone or Steele, the Linear B tablets were written in soft clay, so the writing was not usually preserved. But when the Mycenaeans were attacked their clay tablets were baked in the fires that burned their sacked cities. Through destruction they were saved, and even though the Bronze Age did not endure, these tablets did.

I brought up this similarity in our conversation, since I had just learned about Linear B and the Mycenaeans. Of course I didn’t say that I had just learned about it. I had that unfortunate, and yet not at all uncommon trait, often found among certain excruciatingly learned college students, that make them take on all the ugly characteristics of the nouveau riche. I was falling over myself to show off my flashy and newly acquired wealth of knowledge.

He was patient with me. He was always encouraging and never condescending, even though I probably said horrible things like, “Have you ever heard of the Minoans?” He probably forgot more about ancient history than I will ever know, but in spite of that, he always engaged me in conversation and treated me like an equal, even though he probably shouldn’t have. It might have contributed to this pretentious streak in me.

He managed to show me that he was older and wiser without having to say so. He showed me by example. He was well-educated, well-read and well-travelled, but he was also very humble. He was able to interact with anyone, on pretty much any level. I remember watching him talk to people with very little education. They asked him a question that seemed ridiculous to me. I sneered. He answered with respect. Even though I was at a point in my life where I was kind of looking for things to sneer at, this made a big impression on me. Having knowledge is not the same thing as having wisdom. He had both.

Side note – this book, and the story behind it does notch one small, and perhaps meaningless victory on the side of real books in their struggle against their younger, electronic brethren. Even if you think that e-books are the way of the future, it is hard to argue against this equation:

Shrapnel in a hardcover = family heirloom.

Shrapnel in a Kindle = trash.

You do the math.

On a separate bookshelf my grandfather also had just about everything ever published by Wendell Berry. Often multiple copies (he gave them away). They were not with the rest of the library. No, these books he kept in his bedroom. When he was very sick near the end of his life, my mother bought him some of Berry’s novels on audio-book. He was too weak to sit up and read them but he still enjoyed listening to them.

Wendell Berry was my grandfather’s favorite author, that much is certain, but he was also a major influence on his life and personal philosophy. They shared a lot of similarities: they were both roughly the same age, both from Kentucky, both concerned with environmental issues and both champions of the woods. My grandfather saw it as his personal mission to ensure the protection of trees, since trees are growth and trees are life and future, and trees are everywhere in danger. This was why he turned his 500 acre plot of land into a tree farm, and Wendell Berry’s influence was very evident in all of this. My grandfather was certainly able to think for himself, but he also gratefully and graciously acknowledged his intellectual debts, and gave credit where credit was due. For him, part of this acknowledgement was encouraging me (and just about everyone else he talked with) to read Wendell Berry books as well.

Naturally, I thought of all this when I saw my grandfather’s Wendell Berry books. I thought of the many Wendell Berry books he gave me over the years that remained unread on my bookshelf, and I thought of the many walks through his woods that my grandfather wanted to take with me. I usually turned down the offer. I had more important things to do. If I went, I went unwillingly; usually preoccupied with everything else that was going on in my life. Too preoccupied to simply look and listen and enjoy the quiet that isn’t really quiet, and to hear the birds and the wind and the other sounds of the woods. He saw something in the woods that I didn’t see (mostly because I was unwilling to look). But he wanted me to see it. He wanted everyone to see it.

I thought of the time my grandfather took me to Wendell Berry’s farm for a seminar/workshop on trees. I didn’t want to go. I had not read any of Wendell Berry’s books, and spending a morning sitting outside, talking about trees did not seem like much fun to me at all. But he insisted. “Trust me,” he said, “you will enjoy it.” At first, I didn’t really enjoy it. It was exactly as I thought it would be. Sitting outside, listening to a lecture about trees. But then I started to actually listen, and realized that this was not just a lecture about trees. Mr. Berry started talking about invasive species, and from there he went on to philosophy, and from there to politics, in the abstract, and from there deeper into politics in a very real and tangible way. He started talking about American foreign policy and the war in Iraq. I was shocked – from trees to Iraq in a few deft, fascinating steps. And this was before everyone was talking about the war in Iraq, or at least before they were talking about it in this way. And this was on a farm in Kentucky, not in New York City or in San Francisco.

My grandfather was right – I did enjoy it.

Soon after that my grandfather bought me a copy of A Timbered Choir, and this time I actually read it. I discovered that my grandfather knew what he was talking about, and I wished, as with so many other things, I had listened to him earlier. Now I see what he saw in the woods, but now I cannot walk through the trees with him. Now I can only walk alone. Still, there are many things that help me remember him, whether walking through the leafy trees, or leafing through the books in his library, and I am thankful for them all.

“We have walked so many times, my boy,

over these old fields given up

to thicket, have thought

and spoken of their possibilities,

theirs and ours, ours and theirs the same,

so many times, that now when I walk here

alone, the thought of you goes with me;

my mind reaches toward yours

across the distance and through time.”[1]

[1] Berry, Wendell. ‘We have walked so many times, my boy.’ From A Timbered Choir: The Sabbath Poems 1979-1997. (New York: Counterpoint, 1998), 45.